Religion Has Become A Luxury Good For The Middle Class, Married College Graduate With Children

(ANALYSIS) I’m in absolutely no sense a biblical scholar. I’m nothing more than a lay preacher who was called by a local American Baptist congregation because I was willing to fill the pulpit each Sunday. I took about five courses in the Bible in undergraduate.

I don’t remember a lot about those courses, but a handful of things have stuck with me. Let me get just a little bit preachy for a second. (And forgive me for any heresies).

One idea that I just can never shake is that one of the central themes in the Gospel of Luke is the great reversal. It’s most succinctly stated in 13:30, “Indeed there are those who are last who will be first, and first who will be last.” It’s all over the text.

The Magnificat of Mary, “He has brought down rulers from their thrones but has lifted up the humble.” (Luke 1:52).

“For all those who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.” (Luke 14:11)

And, of course, “Jesus answered them, ‘It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance.’” (Luke 5:31-32.)

The way that I understand Christianity is that Jesus was especially concerned with people on the margins of society. The sick, the poor, and the outcasts were high on his priority list. Thus, churches (being the extension of Jesus’ ministry), should focus their efforts on those exact same people.

But the data says that is not happening. Just the opposite in fact. Religion in 21st century America has become an enclave for people who have done everything “right.” They have college degrees and marriages and children and middle-class incomes. For those who don’t check all those boxes, religion is just not for them.

I’m going to stop quoting Scripture now (not my strong suit) to describing the data (which is way more comfortable for me). The conclusions are unmistakable: Religion has become a luxury good, and that’s leaving most of society on the fringes, yet again.

Let’s start with that old chestnut that I roll out from time to time — the basic relationship between education and religious disaffiliation. This is 15 years of the Cooperative Election Study. These samples visualized here represent over 570,000 total responses, and in many years, the individual sample size is north of 60,000.

It doesn’t take a statistical wizard to figure out the general trend line here. People with higher levels of education are less likely to identify as atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular when it comes to religion. Yes, if you just include atheists and agnostics, the trend does reverse itself. But nonreligious people are not just atheists and agnostics. In fact, most nonreligious people are nothing in particular when it comes to religion. That’s a point I make in “The Nones” and also every time I talk about this stuff.

More educated people are more likely to claim a religious affiliation on surveys. It’s true in every single wave of the Cooperative Election Study. It’s also the case in the Nationscape survey, which has 477,000 respondents. They even have 4,000 people with doctoral degrees in their sample.

The most likely to be nonreligious? Those who didn’t finish high school. As education increases, so does religious affiliation. The group with the highest level of religious affiliation is those with a master’s degree. I think this is likely due to the fact that the majority of folks with master’s degrees are in not purely academic pursuits. Instead, they earn graduate degrees in things like education and business. But that’s a discussion for another day.

Of those with doctorates, 24% are nonreligious. That’s the same rate as those with a four-year college degree. Again, it’s hard to look at these numbers and make some big claim about how education chases people away from religion.

Obviously, affiliation is just one piece of the puzzle, though. Religious attendance is another key component to the religiosity story. So, I did the same general analysis with the CES data, but this time just focused on those who attend religious services weekly. Again, all 15 waves.

Their trend is just as unmistakable: Those who are the most likely to attend services weekly are those with a graduate degree. The least likely to attend are those with a high school diploma or less. And these aren’t small differences, either. The last few years have seen nearly a 10-point gap in attendance from the bottom to the top of the education scale.

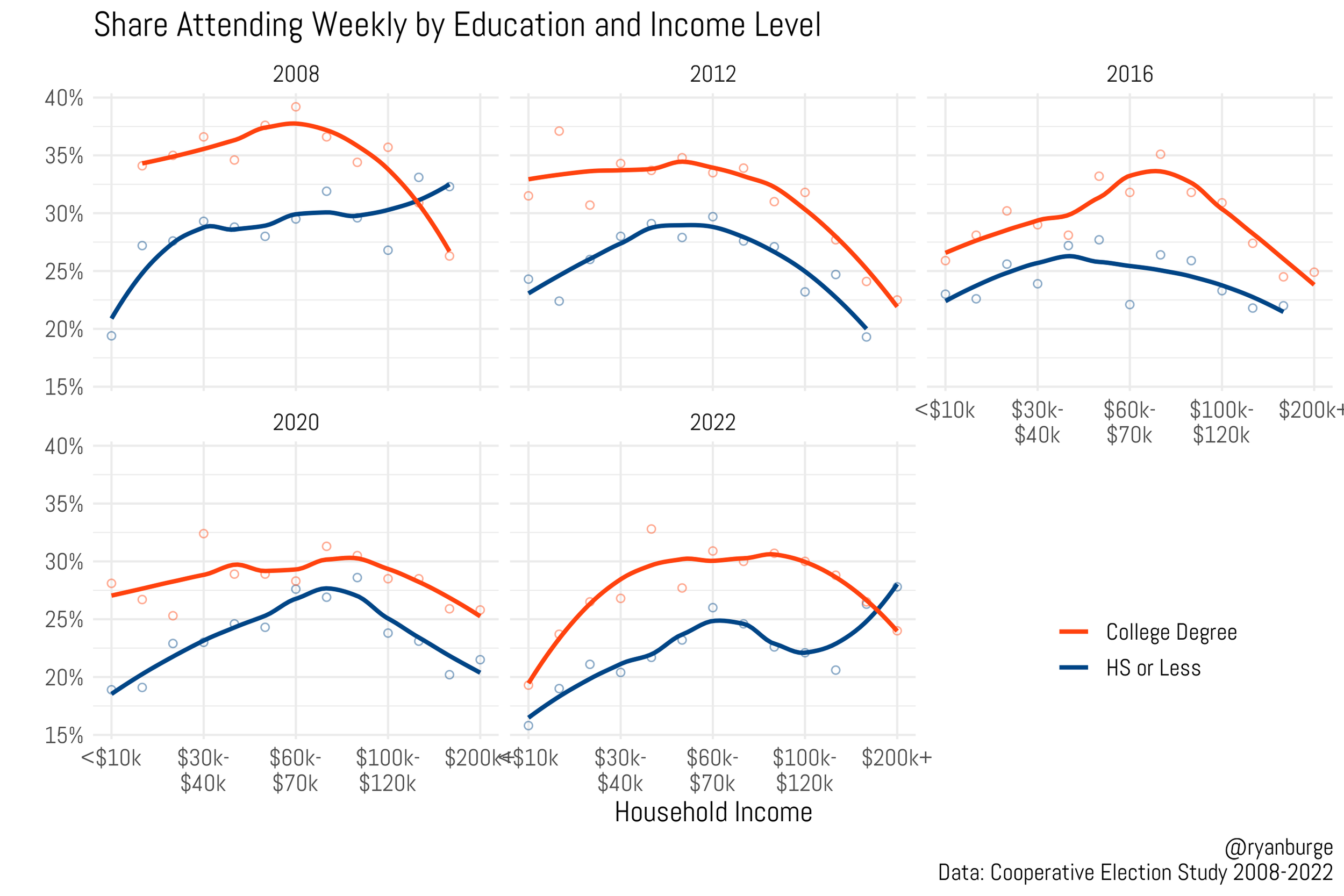

Let’s take this a step further and inject income into the mix as well. So, I divided respondents into those with a high school diploma or less and those with a four-year college degree or more and then calculated the share who attend religious services weekly across the income spectrum.

The first to note is that college educated people attend church at higher rates than those with a high school diploma or less. That’s consistently the case across almost all income brackets. There are a few little squirrely things that happen at the very top end of the income spectrum, but that’s probably due to small sample size.

But notice the overall shape of the orange lines, especially in the last few years of the Cooperative Election Study. They are curvilinear in shape — meaning low on the edges and high in the middle. That’s certainly the case in 2016, 2020 and 2022.

That tells an interesting story about the interaction of income and religious attendance. The group that is the most likely to attend services are not the poor, nor the wealthy. Instead, it’s people who smack in the middle of the income distribution. This analysis points to the following conclusion: The people who are the most likely to attend services this weekend are those with college degrees making $60K-$100K. In other words, middle class professionals.

Let’s throw another factor into the mix now — marital status. The imagined ideal for many for a good American life is a college degree, good job, stable marriage. Does religion have any place for those who are not married? Or are divorced or separated?

The Cooperative Election Study only asks about current marital status, so if someone has been divorced and remarried, that wouldn’t really show up in this data, by the way. But, good gracious, this is a crystal-clear result. Married people are much more likely to be in a religious service than those who are divorced, separated, or never married.

And these are not small gaps, either. Among 40-year-old married people in the sample, nearly 30% are attending services weekly. Among those who are separated, divorced or never married — it’s half that rate: just 15%.

That gap persists all the way through the life course, too. Even among 60-year-olds, it’s still there. About 30% of married retired folks are in churches; it’s just 20% of those who are not married. Marriage leads to much higher levels of religiosity — at any age.

One last little bit of analysis before I stop, just put a finer point on this. I divided the sample into four groups based on married or not married and parents of children or not, then calculated the share attending weekly.

The clear outlier here is folks who are married with children. Among those who fit both criteria and are under the age of 30, 37% are attending weekly. That does begin to decline as the age category moves up. I am guessing that’s because folks who have children later in life tend to be less religious, but that’s just a hunch.

Among those who are married without children, attendance is fairly high in their mid-20s. But then it drops down to being no different than those who are not married and have no children or are not married but are parents.

These results are hard to ignore and should sound some major alarms for any person of faith who is concerned about the large state of American society. Increasingly religion has become the enclave for those who have lived a “proper” life: college degree, middle class income, married with children. If you check all those boxes, the likelihood of you regularly attending church is about double the rate of folks who don’t.

This is also troublesome for American democracy, as well. Religion, at it’s best, is a place where people from a variety of economic, social, racial and political backgrounds can find common ground around a shared faith. It’s a place to build bridges to folks who are different than you. Unfortunately, it looks like American religion is not at its best.

Instead, it’s become a hospital for the healthy, an echo chamber for folks who did everything “right,” which means that it’s seeming less and less inviting to those who did life another way. Do I think that houses of worship have done this on purpose? Generally speaking, no. But they also haven’t actively refuted this narrative.

I was always told that the job of a preacher is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable. Maybe we need a lot more of the latter going forward.

Ryan Burge is an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University, a pastor in the American Baptist Church and the co-founder and frequent contributor to Religion in Public, a forum for scholars of religion and politics to make their work accessible to a more general audience. His research focuses on the intersection of religiosity and political behavior, especially in the U.S. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanburge. Subscribe to his “Graphs about Religion” column on Substack, where this post first appeared.