Orthodox Alaska Part 1: Once An Evangelical Church, This Alaska Parish Has Become An Orthodox Hub

EAGLE RIVER, Alaska — At the base of the Chugach Mountains a half-hour drive north of Anchorage, on Monastery Drive, the tolling of a bronze bell pulses through the crisp Alaskan air before every service, up to five days of the week.

Parishioners of St. John Orthodox Cathedral then crunch across powdery footpaths from their surrounding wooden cabins toward the church. Founding members purchased the church property in 1972 from a Catholic monastery — the Catholic monk and mystic Thomas Merton once visited — and slowly bought the surrounding residential properties to fill with their own families. The ritual of answering the call to prayer on foot feels like going back to a simpler time, to a village linked by lifelong relationships before cars and suburbia disrupted communities and families with individualism and commercialism.

But alas — the present isn’t a simple time to live in after all, even in the beautiful Alaskan woods. Despite a shared Orthodox tradition, Russia is dropping bombs on Ukraine; some women are struggling to accept a faith that reserves some leadership roles for men; some kids are questioning their gender; gay Christians across a range of theologies on sexuality often feel vilified; traditional Christians feel harassed and willfully misunderstood by activists on sex and gender themes; the COVID-19 virus isn’t disappearing, and neither are suicide, anxiety or depression; politics is polarizing church communities; and much more.

St. John Orthodox Cathedral in Eagle River, Alaska. Photo by Meagan Clark.

“What our young people are facing is what we’re facing, and who’s going to address it?” asks Father Marc Dunaway, the priest in charge at St. John’s. I’m sitting at his kitchen table blowing on a mug of hot lemon ginger tea while he boils a pot of eggs to prepare a salad for dinner. His wife Betsy asks me if I need anything. She’s barefoot, but I’m warming my hands on my mug. It’s -20 degrees Fahrenheit outside. In their living room hang icons of Jesus, Mother Teresa (a Catholic saint) and Martin Luther King Jr. — “a picture, not an icon,” Father Marc clarifies about the MLK portrait.

“The church’s tendency in my observation is just to be ultra conservative. And the tendency of some is just to pull into a kind of like a shell and almost go the way of the Amish or something. I mean, really!”

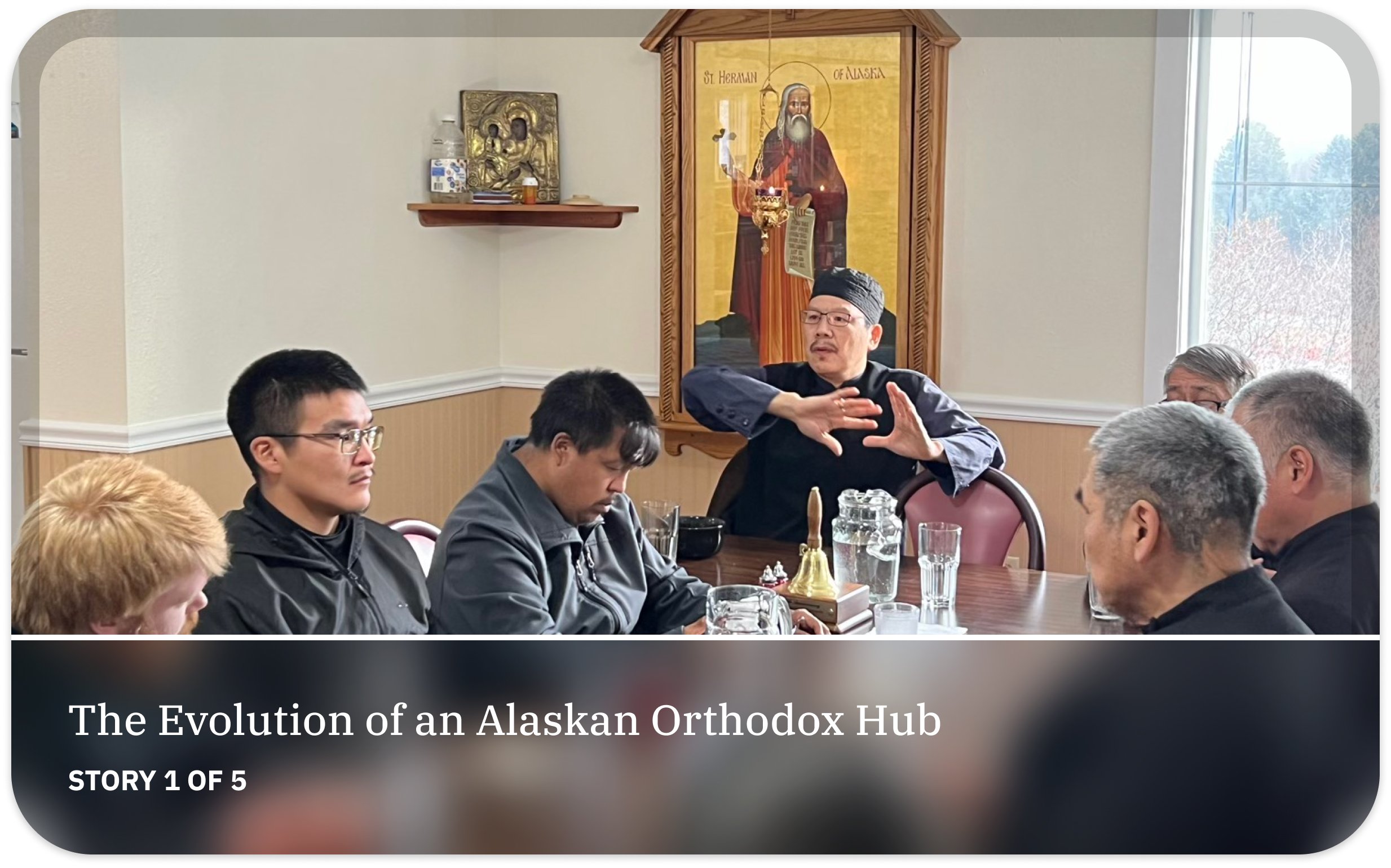

He’s a bit exasperated, but he’s also committed to thinking through ideas to help Orthodox Christians thrive in the modern world. At the same time, St. John’s, within the Antiochian diocese, has become a pan-Orthodox hub attracting visitors from the spectrum of Orthodox traditions, from the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia to the Greek Orthodox Church.

Father Marc Dunaway (center) reads the gospel selection during the Divine Liturgy Sunday morning service. Photo by Meagan Clark.

Each year for 25 years, the Eagle River Institute at St. John’s has hosted Orthodox scholars to address lay people about topics in Orthodoxy relevant to their everyday life. More recently, the lectures are posted online in videos and podcasts. Since 2020, they have partnered with the International Orthodox Theological Association, a new forum for Orthodox scholars and supporters to present papers and provide expertise on theology, liturgical practice and all kinds of church matters to not only lay people but also monks and bishops — the only leaders in Orthodoxy who have the authority to issue official statements or alter church practices.

“We need scholars, monks and bishops, not just monks and bishops — a three-legged stool, as it were — to help the church,” Dunaway says.

Father Marc Dunaway honors the dead in the cemetery of St. John Orthodox Cathedral, and in particular Archimandrite Lazarus Moore, who was an Orthodox missionary priest who served in Palestine, Transjordan, India, Greece, Australia, California and Alaska before his death in Eagle River in 1992. Photo by Meagan Clark.

From Aug. 1 to 5, the Eagle River Institute is bringing together three scholars to provide lectures and forums for lay people, likely about 50-70. This year’s theme is “experiencing God in Orthodox worship,” a topic that has attracted several evangelicals as well. Most attending this week are locals — flights are unusually expensive this summer, and the pandemic has remained prohibitive for some — but the week culminates each year with a pilgrimage to Spruce Island, where North America’s first Orthodox saint, St. Herman, lived alone in a cave devoted to prayer and supporting spiritual and material needs of Alaska Natives. Today St. Herman’s Seminary on Kodiak Island trains mostly Alaska Native seminarians to address poverty, alcoholism, depression and other challenges in their villages, as well as learn Orthodox theology, chant and liturgy.

The frozen tundra’s introduction to Orthodoxy began in the late 1600s when Russian frontiersmen brought their faith, built small chapels and married Native Alaskan women, baptizing them and their children. By 1794, the Russian Orthodox Church answered requests to send priests and established the first mission church in North America on Kodiak Island. Five saints from this period (St. Herman, St. Tikhon, St. Peter the Aleut, St. Innocent and St. Jacob Netsvetov) are some of the earliest and most concentrated number of Orthodox saints in North America, making Alaska a pilgrimage destination for not only American Orthodox Christians but also visitors from Finland, Russia, Serbia and more.

A documentary by Orthodox filmmakers called “Sacred Alaska” is currently wrapping up production and will feature scenes from more than a dozen historical Orthodox “centers” in Alaska. The production team also visited St. John’s.

While less than 1% of Americans identify as Orthodox Christians, 5% of Alaskans identified as Orthodox in 2014, according to Pew Research. And while the number of regular attendees at Eastern Orthodox churches in the U.S. has declined 14% from 2010 to 2020, the number of parishes grew 3% over the same decade, according to the latest data in the 2020 Census of Orthodox Christian Churches. Several Orthodox parish priests, especially in evangelical strongholds like the Bible Belt, report increases in seekers and converts over the past year as the pandemic has continued to recede. This is particularly true of Antiochian Orthodox and Orthodox Church of America parishes, which tend to welcome converts with less ethnic ties abroad.

Under Father Marc Dunaway’s leadership, the St. John Orthodox community is hosting engagement between Orthodox Christians and evangelicals and aspiring to modernize the church in ways that few parishes are equipped for.

Father Marc Dunaway and his wife, Betsy Dunaway, celebrate Thanksgiving Day with their kids and grandkids in Eagle River, Alaska. Father Marc read a selection from “The Hobbit” during a time of sharing thoughtful quotes and reflections for discussion.

Photo by Meagan Clark.

Evangelical beginnings

As I enter St. John Orthodox Cathedral on a Sunday morning in November, the scent of incense mixes with the Alaskan birch wood constructing a geometric dome, where some Orthodox churches would place swirling frescoes of saints. The birch was cut and milled from just 30 miles up the road. The narthex, or entrance room, has a long coat rack to hang parkas, books for sale including popular memoirs about the community written by founding members — though no one let me pay and insisted on gifting copies — and pamphlets of the liturgy and church events calendar that welcome visitors and pilgrims. The chanters stand among the first pews facing the altar rather than separately from the congregation, and they sing as if translating the liturgy into hymns.

Many parishioners join in the singing. The wooden icon screen parts in the middle to reveal an icon of Jesus’ resurrection. Rather than doors that close to separate the holy space of the altar from the parishioners, the icon screen’s gap offers a complete view of the altar, where the priests and his assistants enter to prepare and serve the sacraments. My eyes are drawn to Jesus in the center, where many Orthodox churches would place an icon of Mary holding Jesus. The church feels a little Protestant for an Orthodox church.

And that’s because the church used to be evangelical. It’s a unique Orthodox church in America for its founding by converts to the faith rather than immigrants who brought their faith over from an Orthodox country. The community — dubbed the “Big House” for its meeting place in a large wooden home that looks onto the mountains — began in Eagle River in 1972 as an evangelical ministry for young people to come and live in an extended family-like community, study the Bible and receive mentorship from Harold and Barbara Dunaway, the parents of Marc. The Dunaways met in Kentucky and then spent years working for Campus Crusade for Christ across the country, eventually sent to Alaska in 1968 to minister to military men stationed there.

The Dunaways were inspired by L’abri, an alpine home established by Francis and Edith Schaeffer in the 1950s, to minister to curious travelers and host dinner conversation about philosophical and religious questions. Schaeffer, a prolific writer and Presbyterian theologian, developed an influential film series from his book called “How Should We Then Live: The Rise and Decline of Western Thought and Culture”. The ten-part series sparked political activism among American evangelicals in the 1970s and ’80s, especially anti-abortion campaigning, by defending pro-life views with theological convictions formerly heard mainly in Catholic circles.

In their new community focused on spiritual living, the Dunaways connected with similar groups across the country disconnecting from denominational ties, researching how the experience of church should best be expressed and attempting to identify and discern the earliest Christian traditions. The author and former Campus Crusade minister Peter Gillquist described the spiritual journey of this network, which sprang from former Campus Crusade pastors, in his book “Becoming Orthodox”, now a staple for American Protestants interested in Orthodox Christianity. Gillquist helped to form the Evangelical Orthodox Church, a new denomination, in 1979.

Then in 1987, most EOC churches joined the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Diocese of North America, welcomed by the church’s Patriarch Ignatius IV of Antioch during his visit to Los Angeles that year. Overnight, about 2,000 people become Orthodox, including the parishioners in Eagle River. The Antiochian Orthodox Church dates back to the church of Antioch described in Paul’s letters in the New Testament. Its first followers in the U.S. were immigrants from Syria and Lebanon.

Inside St. John Orthodox Cathedral, some parishioners lift their hands in worship. Photo by Meagan Clark.

From the beginning, lay members at St. John’s soaked up knowledge from Orthodox leaders visiting the parish, including one visit in the ’90s from the Russian Orthodox Patriarch Alexy II on his first journey to Alaska. Today, the community hosts lectures and posts them on their website and YouTube channel, offering educational materials to the church and seekers learning about Orthodoxy online. St. James House across from St. John Cathedral remains a steady part of the community, rotating fresh faces and experiences into the conversations and gatherings.

An Orthodox community open to outsiders

St. James House is large enough to contain separate apartments with kitchens and living areas, and the main living space upstairs with a view of the mountains can accommodate 20-30 people comfortably. Framed group pictures hang on the walls, capturing a moment of each summer the house has operated, a timeline of youth fashion from the ’70s till today.

Parishioners at St. John’s, neighbors and friends join for Thanksgiving dinner at St. James House in Eagle River, Alaska, in November 2021. Photo by Meagan Clark.

During my visit to the community in November, a young couple in their 30s with children manage St. James House, dividing chores, providing some meals, leading discussions and prayers and generally providing a cozy environment for conversation. All the renters, who pay much less than the market rate for their stays in exchange for participating in the community and chores, are men in their 20s.

Three teach at nearby schools, including a private Orthodox school on St. John’s property; some are unemployed looking for jobs and figuring out what’s next for them.

The environment encourages conversation about happenings in Orthodox circles, like the number of converts entering the church and how St. John’s compares to other Orthodox communities. Everyone in the St. James House at this time converted to Orthodoxy from a Protestant tradition.

After the church service, I drive to a brewery in town with Ethan DeJonge, a recent graduate from Grove City College and tenant at St. James House whose parents run an icon-printing business in Michigan. DeJonge converted to Orthodoxy from a journey through Protestant churches at age 11 with his dad; his mom is a nondenominational evangelical.

DeJonge tells me he’s grateful for the St. James community this year because it’s hard to meet Orthodox Christians his age, who seem missing from churches after high school and before marrying. Grove City, a conservative college, was full of evangelicals, Baptists, Presbyterians, Anglicans. In an Orthodox community, he can relax more and discuss the present challenges and trends across the country, the “inside baseball.”

“A lot of times, you'll see converts coming in, and they're super hyped up on it, and they're listening to these very fundamentalist Orthodox people … and they're like, okay, I have to go to a church where every woman has her head covered and she's always wearing a skirt.”

Ethan DeJonge stands in front of St. John Orthodox Cathedral after the divine liturgy on a Sunday morning. Photo by Meagan Clark.

He also encountered the tensions and diversity present in Orthodox American circles today. He recalls one young man, a new convert, who frequently criticized the Greek Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, preferring the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia. At the end of his time at St. James House, the young man began attending the local Greek Orthodox church with a young woman he met on a dating app.

“A lot of times, you'll see converts coming in, and they're super hyped up on it, and they're listening to these very fundamentalist Orthodox people … and they're like, okay, I have to go to a church where every woman has her head covered and she's always wearing a skirt,” DeJonge says. In his experience, hardline fundamentalists either burn out and leave the church or soften as they enter a deeper understanding of Orthodoxy.

According to DeJonge, Orthodoxy is about acquiring the mindset of Christ; neither distracted by rules nor letting secular culture uninterested in Orthodox ideas set the framework for questions like women’s ordination.

At St. John’s, evangelical-Orthodox tradition can perhaps blend into Orthodox traditions. It’s an American Orthodox church after all. “At St. John's, there's always that question like, is this the St. John's thing, or is this an Orthodox thing?” DeJonge says. Maybe both.

Father Marc Dunaway admits St. John’s does things a little differently at times, but he believes that’s an asset drawing in seekers and people unfamiliar with Orthodoxy so greater cooperation among Christians can blossom. He sees his work as ways to counter fundamentalism in the Orthodox church, by helping people see the true faith in the real, messy world and live more like Christ.

“Fundamentalism by its nature is polarizing because it insists on black and white. There’s no gray. That’s one of the characteristics, psychologically speaking, of fundamentalism, I think, that insistence on certainty,” Dunaway says. “And so they have their ways of establishing certainty: I know what the tradition is. I have a voice of authority in this muck. I don’t have any doubt. I could wake up every morning with total certainty about what I believe and what I do and the answer to every question. Well, that’s just not the real world, even in the Orthodox world.”

Part of St. John’s DNA is continuing engagement with local evangelicals — not to convince them to become Orthodox but to encourage dialogue. Last week, Dunaway met with Bishop Alexei of the Diocese of Sitka and Alaska to discuss St. John’s hosting a local evangelical and Orthodox meeting in September in partnership with the Lausanne-Orthodox Initiative, an international movement of evangelicals and Orthodox Christians who want to enhance cooperation and understanding between the groups.

Bradley Nassif, leading academic expert on evangelical-Orthodox dialogue, will address an audience at the Eagle River Institute about what the Orthodox can learn from evangelicals and what evangelicals can learn from the Orthodox.

Evangelical Jonathan Speigel and his wife are the first to arrive at a weekly book club at St. James House led by Dunaway. Speigel has attended for many years and enjoys learning about early church history and praying with the Orthodox group. He now has several icons at home.

“I realize, you know what, at the core, we're the same,” Speigel says. “We develop different approaches to things, different expressions, different understandings … but when we listen to each other, you know, we learn. So I've always had a great time. And I've developed an interest in the ancient church fathers. And of course, they're kind of like, all Orthodox.”

Modern Orthodox collaboration

Perhaps more than any other partnerships of St. John’s, Father Marc Dunaway is most excited when he talks about the International Orthodox Theological Association and Fordham University’s Orthodox Christian Studies Center in New York, which both aim to articulate and examine Orthodox responses to modern challenges.

Last year at the Eagle River Institute, scholar of modern Orthodoxy at Western Washington University Carrie Frederick Frost lectured about the Orthodox tradition of women not receiving Communion while menstruating, arguing that the ancient Jews and early Christians did not understand the science of periods when they formed purity rituals and practices for the sacraments.

At the Eagle River Institute this week, Teva Regule, president of IOTA and a scholar from Boston College of liturgical history and theology, will speak about liturgical renewal and what parishes can learn from monastic life.

From a coffee shop around the corner from St. Mary’s Orthodox Church in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Regule explains that IOTA’s founding was inspired in part by the work of the Orthodox Theological Association of America, formed in 1966 by clergy who taught at seminaries to exchange views. Today, more and more Orthodox lay people like Regule have doctorates in church-related matters and are asking questions like, How can we increase cooperation among Orthodox jurisdictions not only in America but across the world? Divisions in global Orthodoxy are a top concern.

At the first IOTA meeting in Romania in 2019, “the energy was really palpable,” Regule says. “All of the sudden you can recognize and know, even though you have a totally different kind of cultural setting, that you’re part of one faith.” About 300 people attended. The next meeting is scheduled in January 2023 in Greece. Dunaway hopes to attend with his son and return with more perspective to share with St. John’s.

Meagan Clark is the managing editor of ReligionUnplugged.com. She has reported for Newsweek, International Business Times, Dallas Morning News, Religion News Service and several other outlets including in India. She is a 2024 Master’s Candidate in Religion and Journalism from New York University, has a master’s degree in Religion and Public Life from Harvard Divinity School (‘22) and is a board member of the Associated Church Press. Follow her on Twitter @Meagan_Salia.

Up Next in this Collection

-

While less than 1% of Americans identify as Orthodox Christians, 5% of Alaskans identified as Orthodox in 2014, according to Pew Research. And while the number of regular attendees at Eastern Orthodox churches in the U.S. has declined 14% from 2010 to 2020, the number of parishes grew 3% over the same decade, according to the latest data in the 2020 Census of Orthodox Christian Churches.

-

Several young Orthodox converts who live at the St. James House, a self-directed program for young Orthodox adults, kept asking me during my visit last November if I had met Joe, the beekeeper. From what I had gathered, this guy named Joseph “Joe” Dunham, 68, was a living legend of the Eagle River community. He sounded quirky. I had to meet him.

-

The arrival of St. Herman and a group of eight monks on this island on Sept. 24, 1794, planted a seed for the Orthodox Church on the continent. Since then, Alaska has been a spiritual cradle of Orthodox Christianity in North America.

-

Orthodox Christians in North America and around the world already are venerating the Alaskan matriarch for her care and concern for abused women.

-

From the beginning of their journey into the Orthodox faith, Meghan and Michael Jones were metaphysically connected to Alaska. But their sense of calling to spread the gospel, expand the church and launch socially redemptive initiatives eventually led the couple and their four children to Fiji.