Orthodox Alaska Part 3: A Seminary That Serves As Kodiak Island’s Arctic Willow

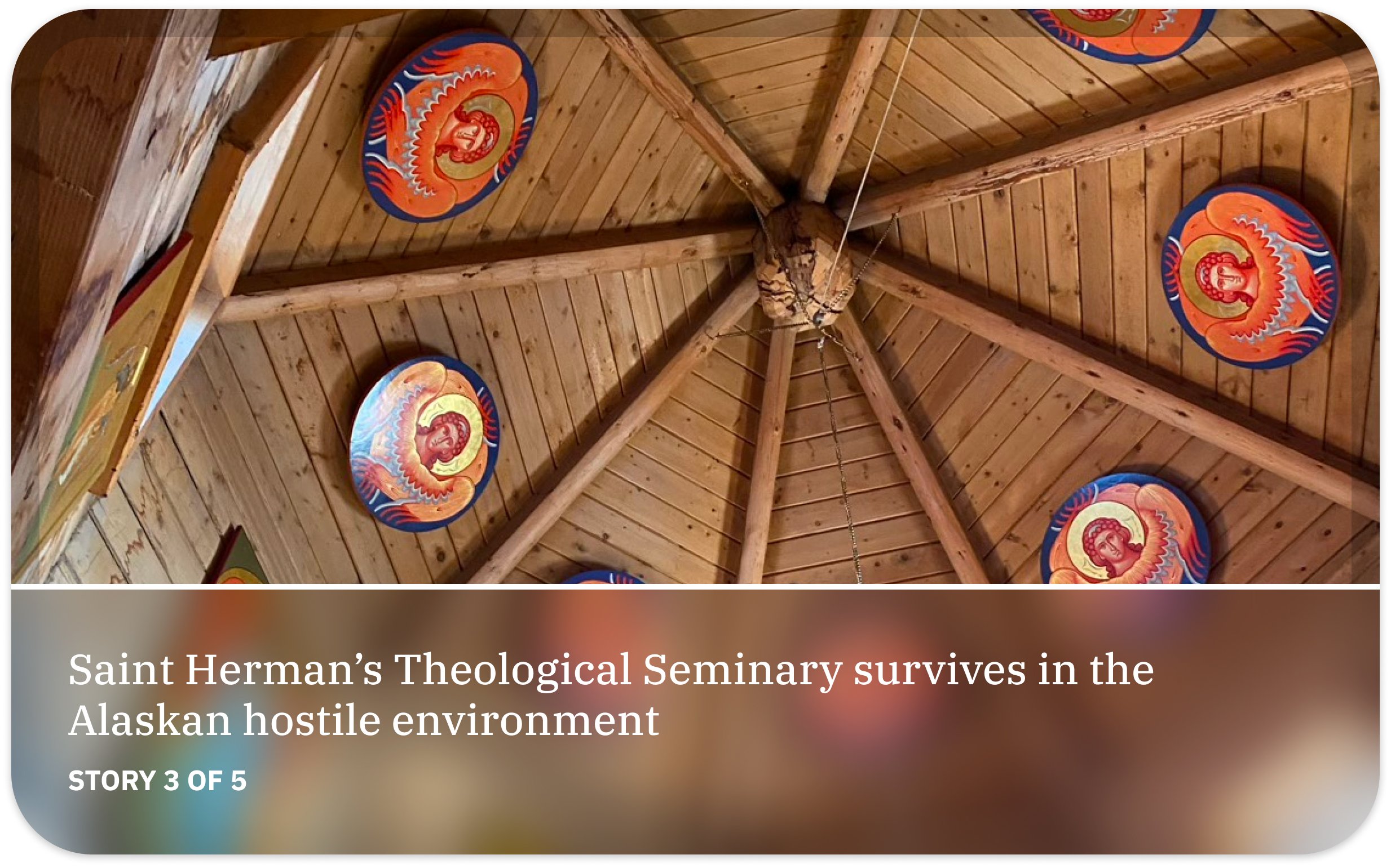

The ceiling of All Saints of Alaska Chapel. Photo by Jovan Tripkovic

The Arctic Willow

by Varlaam Shalamow

The willow flowers, packed in snow,

The willow must hurry,

To live like a bird, like a man

If it really wishes to live.

KODIAK ISLAND, Alaska — Kassiana Sonday wakes at 5 a.m. most days to rush to the early chapel and help prepare for morning prayer at St. Herman’s seminary, a unique and boutique Orthodox educational outpost on this remote island in Alaska.

She spends the rest of her day in classes, homework, meals, basketball practice and more chapel services — evening vespers — at St. Herman’s seminary. Despite being one of only a dozen students at St. Herman’s, she says she enjoys the community at this institution.

“There is something so spiritually edifying about life as a student at St. Herman's,” she says, while sipping a cup of tea in the cafeteria on campus. “The days are long and packed but filled with such spiritual reward.”

How a seminary landed on Kodiak Island

The arrival of St. Herman and a group of eight monks on this island on Sept. 24, 1794, planted a seed for the Orthodox Church in the region. Since then, Alaska has been a spiritual cradle of Orthodox Christianity in North America.

Although the first Orthodox parish was founded in 1768 in St. Augustine, Florida, by the first colony of Greek immigrants, Alaska has positioned itself as an “Orthodox country.”

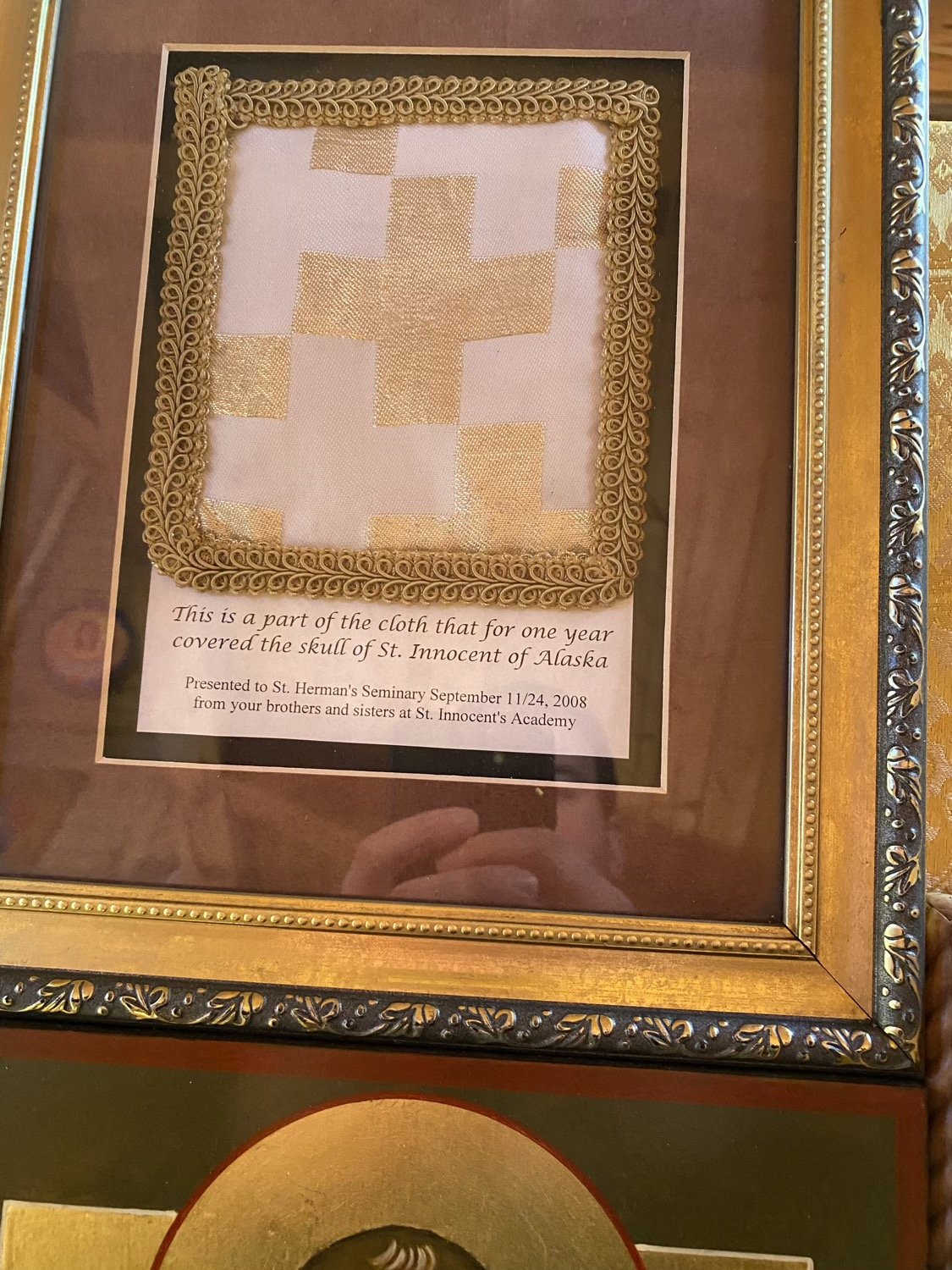

The reason for Alaska’s disproportionate influence is that it gave the Orthodox world five saints: St. Herman of Alaska, St. Peter the Aleut, St. Innocent, St. Hiermonk Juvenaly and St. Jacob Netsvetov. These saints are receiving pan-Orthodox recognition after they were canonized. Increasingly, Orthodox theologians and clergy are discussing the canonization of Matushka Olga Michael, an Alaska Native woman known as a protector of abused women.

Besides planting a seed for the Orthodox Church in Alaska, St. Herman planted an idea of Orthodox education that would eventually lead to the establishment of the Orthodox theological seminary named after him and located here on this remote island outpost south of Anchorage in the Gulf of Alaska on the Pacific Ocean.

The roots of St. Herman Theological Seminary trace back to the early 19th century in Unalaska, an Aleutian island 800 miles west of Anchorage. In 1804, Hieromonk Gideon established the first bilingual theological training program in Alaska. For the next couple of decades, few other theological training programs emerged. However, in 1826, a local parochial school was founded in Unalaska.

Father Noah Andrews prays during morning service. Photo by Jovan Tripkovic

The founder of the school was Father John Veniaminov, a famous teacher and priest who translated texts from Russian into local Alaskan languages to create bilingual curriculum. The curriculum of the school was similar to the curriculum of St. Herman seminary. Students were taught in Russian and Unangan, which is a dialect of the tribal Aleutic language.

Orthodox Russian roots

In later decades a renewal of Orthodox education in Alaska began. By the early 20th century, nearly 30 schools had been established, all financed by the Russian Missionary Society and the Russian Orthodox Church.

Unfortunately, the October revolution of 1917 and Vladimir Ilyich Lenin’s rise to power and anti-religious government halted funding for these schools and the missionary work in Alaska. For a bit more than half a century, Orthodox education entered a dark period in the northernmost state.

Until the early 1970s, no Orthodox parochial schools operated in Alaska. Education of clergy and faithful people became self-directed. A few teachers and instructors came to Alaska to conduct lessons on Scripture and Orthodox liturgy. Despite these hard times, the number of Orthodox believers in Alaska grew, as 91 Orthodox parishes now dot the Alaskan landscape.

In 1972, at a meeting on Kodiak Island, the Diocesan Assembly voted unanimously to establish a pastoral school with a mission to train Alaskan clergy. The beginning of St. Herman Seminary led to many difficulties. The institution did not have proper funds, faculty, campus or even a bishop to oversee the seminary. The first campus of St. Herman Seminary was a rented property at Wildwood Station, a former military-owned building. The location of the first campus was near Kenai, a town further north and closer to Anchorage. However, in 1974, the seminary moved from Kenai to Kodiak, returning back to St. Herman’s roots.

Ups and downs through decades

The school has seen success in subsequent years. The State of Alaska Department of Education accredited the school, and the Holy Synod recognized the seminary as a theological institution of the Orthodox Church in North America.

During the 1980s, the seminary rapidly expanded its academic program and reputation in the Orthodox world. In 1989, the seminary was authorized to grant bachelors and associate degrees. Additionally, in 1985, the seminary established an alcohol-counseling training program to prepare clergy to serve native communities plagued by alcoholism.

But if the ’80s were a boom time, the following decade turned difficult for the St. Herman Seminary. During the late 1990s, the institution lost its accreditation, which was replaced by state authorization with an exemption to operate as a religious institution. Additionally, the student population dropped drastically to less than 10, and the campus became unrecognizable.

All Saints of Alaska Chapel located on campus. Photo by Jovan Tripkovic

The Holy Resurrection Church in Kodiak, Island. Photo by Jovan Tripkovic

The Crucifix in All Saints of Alaska Chapel. Photo by Jovan Tripkovic

But now it seems that St. Herman Theological Seminary is attempting to make a comeback. Under the new leadership of Archpriest John Dunlop and later Father Vasily Fisher, the seminary has expanded its student body to 12 students and reorganized its curriculum, including practical aspects. The reasons for this shift were the COVID-19 Pandemic, needs of the Orthodox Church in Alaska and drug/alcohol addiction among Alaska Natives.

Father Dunlop, now dean emeritus of the school, noted heavy turnover in bishops during his time in Alaska. With that kind of turnover, the bishops had different viewpoints on the seminary regaining accreditation. “St. Herman is a vocational and pastoral school, uniquely training pastors, readers, catechists and educators for Alaska,” he said in a phone interview with ReligionUnplugged.com. He said the school offers clinical pastoral education with a certificate. “We also offer regional drug and alcohol counselor training, which is through the state of Alaska.”

Although the school remains small, it is able to stay afloat because it operates lean in a place where costs are low. One woman who heads the school cafeteria said the school spends $600 a week to feed roughly 25 people three meals a day.

“I don’t see that the enrollment will drop in the future,” said Dunlop. “I would see it as increasing, given our new Bishop’s interest and commitment in the seminary.” After serving the school for 25 years, he said enrollment has held steady in the past few decades and demand is strong. Of the 91 Orthodox parishes in Alaska, only 30 have resident priests.

The school isn’t required to file IRS 990 forms because it’s registered with a religious exemption. The budget is close to $500,000 a year according to some sources, although school leaders say they can’t disclose more financial details without a blessing from a bishop.

School leaders say the institution relies on small donations from the roughly 6,000 people who receive its newsletter to support its annual fundraising campaign and scholarship fund. Some Russian-American nonprofits also donate to support the four full-time and three adjunct faculty members.

Students attend morning prayer. Photo by Jovan Tripkovic

Finding equilibrium

Today’s curriculum is 50% academic and 50% practical. This concept makes the St. Herman Theological Seminary unique among Orthodox institutions in the world. The academic part still covers courses about Scripture, Orthodox liturgy and the sacramental life of the Orthodox Church. The practical part includes bilingual instruction and Native American language courses. All students of the seminary receive bivocational training: theological and drug and alcohol counseling. Bilingual training and dual education show that St. Herman Theological Seminary builds upon rich academic and spiritual traditions.

Although the student body remains small, it seems most of the students are fully committed to their academic studies and spiritual development, as well as their calling to serve Orthodox communities in remote areas of Alaska. The student demographic is pretty diverse, having both Native American cradle Orthodox and former evangelicals and Moravian believers who are now Orthodox converts.

In addition to the seminary’s multiethnic environment, the age range of students varies, from early 20s to those in their 70s. The reason for that is the regional nature of the seminary, which was established with a mission to train Orthodox clergy in Alaska.

Father Noah Andrews after morning service. Photo by Jovan Tripkovic

All Saints of Alaska Chapel's iconostasis. Photo by Jovan Tripkovic

In recent years, the need for priests in remote Native Alaskan villages became tremendous, opening doors for creative solutions. Many older seminarians at St. Herman’s are already retired and decided to pursue the priesthood as a second career.

“In 10 years, we’ll expand our programs,” said Father Dunlop during a phone interview with ReligionUnplugged.com. “I think overall, our dioceses will have a good stable period ahead of it, and because we have a tremendous need for clergy, there’s a real need for the seminary and for the work we’re doing — not only in producing clergy but also catechists, readers and deacons.”

Since its foundation, the situation has not changed. It’s clear that Orthodox communities in Alaska could not expect priests from the contiguous states to come to Alaska to serve in remote Orthodox villages, often without proper accommodations, compensation and language skills — since many Alaska Natives do not speak English.

Instead of inviting clergy from other states, the alternative was to send Orthodox Alaska Natives to elite Orthodox seminaries such as St. Vladimir’s Seminary in New York or St. Tikhon’s Seminary in Pennsylvania. Financially and logistically, this solution appeared unsuitable. Rather, Orthodox Christians in Alaska believe St. Herman’s Seminary is a good starting place for students who can then pursue graduate work at Orthodox seminaries on the East Coast if they so choose.

“There’s kind of a mixed feeling as to our ability in terms of finances and all these kinds of things to reach the accreditation goal,” Dunlop said. “In the past we partnered with both St. Vladimir’s and St. Tikhon’s Seminary. There’s also the sense of collaboration with them. There is a possibility in the future for some kind of umbrella relationship. We would be sort of under the thumb in terms of accreditation. However, we are an undergraduate school, while St. Vladimir’s and St. Tikhon’s are graduate schools.”

Inside All Saints of Alaska Chapel in Kodiak, Alaska. Photo by Jovan Tripkovic

The Orthodox need

Father Noah Andrews is an interesting case study, with a background as an Alaska Native and having spent time in the U.S. Military. His village, Kwigillingok, located in the region of West Alaska by the Bering Sea, is in desperate need of a priest.

“There are four, five parishes in that area,” said Father Dunlop. “A local priest died seven years ago, leaving parishes priestless.” Therefore, faculty of the seminary, with the blessings of the local bishop, decided to accelerate Father Andrews’ study program to ordain him to the priesthood earlier than planned and to send him to Kwigillingok.

The COVID-19 pandemic limited Andrews’ return to his village, but he plans on returning there with his family in coming months. He has seven adult children — two girls, four boys and one adopted son. “Our kids are grown up — they can take care of themselves,” Andrews told ReligionUnplugged.com while showing a map of parishes in Alaska. “My wife and I started talking about the seminary and that we should come for only two or three years a long time ago. When I first saw a deacon serving, it clicked in my mind and I said I want to be a deacon too. I arrived at the seminary in 2018. My first year I became a subdeacon; my second year I became a deacon.”

Other students are pursuing education at the seminary with hopes of addressing the addiction pandemic among Alaskans both spiritually and professionally. “Alcohol and drugs are the biggest problem in villages,” said Andrews. “There are no jobs! Most people were laid off. There are some jobs at the tribal police, but that is it. A year ago we had a class on how to run alcohol rooms, how to help people who are having problems anyway.” He said the goal of the seminary is to train men and women who can go back and try to not only serve in the village but help people who are having problems — not just in the church but outside the church as well.

Alaska Department of Health:

Overdose Deaths by Year (2012-2021)

From 2010 to 2017, with 623 identified opioid overdose deaths, the opioid overdose death rate increased 77%, from 7.7 per 100,000 people to 13.6. The highest number of opioid-related deaths identified in one year was 108 in 2017 (preliminary data), of which 100 (93%) were due to overdose, according to the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services Division of Public Health. Meanwhile, the rates of opioid-related inpatient hospitalizations were 28.5 per 100,000 persons in 2016 and 26.0 per 100,000 persons in 2017, with total inpatient hospitalization charges exceeding $23 million. Some Orthodox leaders in Alaska realize the church can help make a difference on this front.

Tabitha Heckert said she came to the seminary because she wanted to learn more about the Orthodox Church and also wanted to help small communities in Alaska. She believes she can help Alaskan Orthodox communities with abilities in music, knowledge of the liturgy and perhaps a role as an addiction counselor. She said she feels called to serve “because of the great need” she sees in communities.

She said she also appreciates the pace of life in Alaska and at the seminary, going on walks, enjoying bonfires and enjoying fellowship with her seminarian brothers and sisters. “What drew me to the Orthodox Church was the aspect that you never stopped learning or growing and that there is a completeness to it,” she said. “Another thing that really drew me was that you experienced the church with all of your five senses.”

The unique multicultural, multilingual and multigenerational dynamic at St. Herman’s Seminary creates a vibrant student life. Older students usually live with their spouses and kids, while younger students experience college dorm life.

Since the foundation of St. Herman’s Seminary, student life has not drastically changed. It still consists of an academically rigorous program, rich and active liturgical life and extracurricular activities. The studies include church doctrine, liturgical music, liturgics, church Slavonic — not very common in North America among Orthodox seminaries — pastoral field work, canonical tradition, comparative theology, patristics, and theology of marriage.

The Very Reverend Vasily Fisher, Seminary Dean in his office. Photo by Jovan Tripkovic

Seminarians with Dean Fisher (right) during lunchtime. Photo by Jovan Tripkovic

Finding new generations of students

Although dressed conservatively in a similar fashion as Orthodox priests wearing black robes, these young students are not very different from the average college student. A sneak peak into their dorm rooms reveals a lot. The extracurricular activities include arts and crafts, cooking, intramural sports (basketball), and going out to local restaurants and cinema.

One student describes his room as “creative chaos.” A visitor sees packages of ramen noodles, Netflix queues on screens, an Xbox video game console, Star Trek posters on walls and figurines on shelves. These are some of the indispensable parts of their college life.

The calm, serious and ascetic life of the seminary is often interrupted by a young student, Peter Sonday, who with his funny jokes breaks the monotony of Kodiak Island and makes life more bearable. Contrary to what a visitor might expect, his funny prompts are appreciated by students as well as the dean, Father Vasily Fisher, who described Peter as “quite a character.”

Peter’s path to St. Herman’s Seminary was unusual. His sister, Kassiani, and his childhood friends, siblings Brenden and Tabitha Heckert, are all from Orthodox convert families in Kenai, Alaska. When it was time for college, Kassiani, Brenden and Tabitha all applied and got accepted to the seminary. Not wanting to be left behind in his hometown, Peter quickly decided that he wanted to follow his sister and friends. Just a couple of weeks before the academic year started in 2021, Peter submitted necessary documents and was accepted to the seminary. Since then he hasn’t looked back.

In a conversation with ReligionUnplugged.com, Kassiani said her journey to Orthodoxy started when she was a young Protestant:

I was aware and felt the churches and different denominations we were attending felt empty and that we were not worshipping God in the way he requires of us and not to its fullest. So as a family, we were searching together for quite a while.

When we finally came across Orthodoxy, it was an answer to prayer, the fullness of the faith that of what we were searching for my whole life. What really attracted me to Orthodoxy was how full the services are and how we use every portion of our body, as we smell the incense and hear the bells of the censer and the choir singing as the priest and deacon say their petitions and you see the icons. You're venerating them and crossing yourself with the sign of the cross throughout service. It was so beautiful ... and after the first service I attended, I felt this overcoming peace. This is where I want to worship, this is how I want to live. Then I knew I wanted to become Orthodox.

Although she cannot serve as a priest, Kassiani said the seminary is fulfilling her “unquenchable desire to learn about pretty much anything Orthodox, from the dogmas to the orders of service (and) choir/liturgical music.” She said she’s thrilled by the thought she can take that knowledge with her and share it with others.

“Alaska is my home — though I wasn't born here, the Alaskan people are more than family to me,”

“Alaska is my home — though I wasn't born here, the Alaskan people are more than family to me,” Kassiani said. “So the desire to serve the Alaska Diocese and be a help to the communities in Alaska is like giving your time and effort to those you love and care about, especially in a way that is edifying and glorifies God in the process.”

Jovan Tripkovic is a graduate student and teaching assistant at the University of Wyoming and a contributor to ReligionUnplugged.com and other publications.

Earlier in this Collection

-

While less than 1% of Americans identify as Orthodox Christians, 5% of Alaskans identified as Orthodox in 2014, according to Pew Research. And while the number of regular attendees at Eastern Orthodox churches in the U.S. has declined 14% from 2010 to 2020, the number of parishes grew 3% over the same decade, according to the latest data in the 2020 Census of Orthodox Christian Churches.

-

Several young Orthodox converts who live at the St. James House, a self-directed program for young Orthodox adults, kept asking me during my visit last November if I had met Joe, the beekeeper. From what I had gathered, this guy named Joseph “Joe” Dunham, 68, was a living legend of the Eagle River community. He sounded quirky. I had to meet him.

Up Next in this Collection

-

The arrival of St. Herman and a group of eight monks on this island on Sept. 24, 1794, planted a seed for the Orthodox Church on the continent. Since then, Alaska has been a spiritual cradle of Orthodox Christianity in North America.

-

Orthodox Christians in North America and around the world already are venerating the Alaskan matriarch for her care and concern for abused women.

-

From the beginning of their journey into the Orthodox faith, Meghan and Michael Jones were metaphysically connected to Alaska. But their sense of calling to spread the gospel, expand the church and launch socially redemptive initiatives eventually led the couple and their four children to Fiji.