Christian Adoption Agencies Offer Insight Into Impact Of Abortion Bans, Restrictions

Jerry Callens holds a newborn baby in a hospital. Photo provided by Jerry Callens.

“It’s like someone turned a faucet on.”

That’s how Sherri Statler, president and CEO of Christian Homes and Family Services in Abilene, Texas, describes the increase of women with unplanned pregnancies seeking help from her organization.

The numbers started rising last November, after the Texas Heartbeat Act — which bans abortions after the detection of the fetal heartbeat at around six weeks — was enacted in September 2021.

Now Statler anticipates the number of pregnant women in need of help might grow even more after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade last week.

“We expect that Texas is going to be a leader in making abortions incredibly rare,” Statler said.

The nonprofit adoption and foster care agency, which is associated with Churches of Christ, works with about 50 pregnant women per year. Currently the ministry is serving eight women, Statler said, and is corresponding with 12 more.

“We want to help them just live through this pregnancy, and we try to help them envision life beyond the pregnancy,” Statler said. “Most of the time, they’re already two months pregnant before they even come to terms with it. So then there’s seven months, and we say, ‘OK, think about things that only last seven months. It’s shorter than the school year.’”

Case workers and counselors encourage the women they encounter to set future goals they can work toward while pregnant: getting their GED diploma, continuing higher education or pursuing a more stable career path.

Free job training is available through FaithWorks, a mentoring organization started by Churches of Christ in Abilene. Christian Homes and Family Services also works with colleges to advocate for the needs of pregnant students.

But student and teenage pregnancies are not their average demographic.

The nonprofit usually works with women between the ages of 20 and 28 who “meet every definition of poverty that you can imagine,” Statler said. Many already have children or prior pregnancies ended by abortion, and are unable to financially support having another pregnancy.

In 2017, Sherri Statler reminisces about some of the many babies adopted through Christian Homes and Family Services in Abilene, Texas. Photo by Bobby Ross Jr.

“Some of them are already parenting. They have a child or maybe two, and they end up pregnant again,” Statler explained. “And they realize that they have kind of cobbled a life together for themselves and one child, or maybe even … two children, but this third child is going to sink their boat. They just won’t be able to do it with three.”

That’s when her organization steps in.

Pregnant women build an adoption plan with the help of case workers, selecting couples that the Christian organization has already vetted and working out the details of an open, semi-open or closed adoption.

“Our vision is a Christian home for every child,” Statler said. “And whether that Christian home is with an adoptive family, a foster family or maybe even a birth mother whose life was transformed and came to know Christ because of the work that we do — that’s our mission, a Christian home for every child.”

Making adoption affordable

Three states away, in Gainesville, Florida, another nonprofit associated with Churches of Christ has a similar goal.

“Our mission is to come alongside as many moms as possible, to help them decide what’s going to be best for their baby and for them and any other children they may have,” said Jerry Callens, executive director of Christian Family Services.

In 2021, the nonprofit worked with about 135 women facing unintended pregnancies. Most were in similar circumstances of poverty to those described by Statler in Texas. Christian Family Services has placed over 500 children with adoptive families since its founding in 1978.

Callens, an adoptive father of two, understands just how expensive it can be for couples seeking to adopt. That’s why the Florida nonprofit charges couples on a sliding scale.

With a minimum adoption fee of $7,500 and a maximum of $18,000, the agency asks couples to pay 14 percent of their gross annual income.

Some agencies also require adoptive parents to pay for the birth mother’s expenses — even if the birth mother later changes her mind, Callens said. That happens rarely, he added. Nonetheless, Christian Family Services covers those costs.

“The last thing we want is for the family to leave the hospital with empty arms, but also empty pockets saying, ‘we can’t afford to do this anymore,’” Callens said. “So we pay all of mom’s expenses. We don’t ask to be reimbursed; we don’t even tell the family what they are. We simply rely on our donations and contributions and fundraisers to pay her expenses.”

Jerry Callens waits in the hospital with a woman as she voluntarily signs her parental rights away before praying over her. Photo provided by Jerry Callens.

Families from anywhere in the U.S. with an approved home study are eligible to adopt from Christian Family Services. The waitlist is one to two years, with times varying due to specifications from both the prospective parents and the birth mothers.

“The waitlist that fills up the quickest, obviously, is the Caucasian-only baby,” Callens said. “We tend to get more families (on that list). Sometimes we will have to cap that one.” Waitlists for non-White or biracial babies often remain open, he added.

More funerals

With a lower adoption demand for babies of color, health care experts worry that impoverished and minority communities will be disproportionately affected by abortion restrictions or bans that lawmakers will likely enact over the next few months.

In the most recent data available from 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that Black women have the highest abortion rate at 23.8% nationally. For Hispanic women, that percentage is 11.7 and for White women, it’s 6.6.

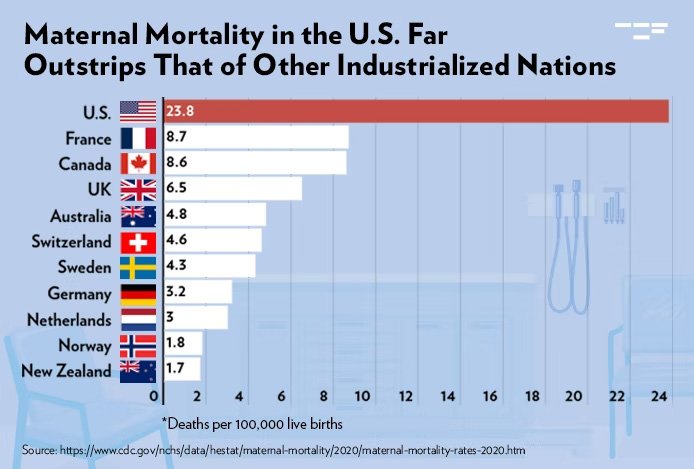

The U.S. also has the highest rates of maternal deaths among developed nations, with 23.8 deaths per 100,000 births, according to The Century Foundation, a public policy research institute. Black women were three times more likely to experience maternal mortality than White women.

A graph of maternal mortality among other developed nations. Graphic from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Verlon Johnson, an expert on health care policy, advocate for health care equity and a member of the Park Forest Church of Christ in Matteson, Illinois, worries that abortion bans and restrictions will have unintended implications on maternal health.

“It is possible that a total abortion ban could actually result in increased maternal deaths, particularly among women of color, women from low-income backgrounds and women living in rural areas,” said Johnson, who worked for 25 years overseeing Medicaid and Medicare programs on a national level. “I think what people don’t understand is that when we’re restricting access to abortion, it doesn’t really decrease the rates of abortion. It actually just increases the rate of unsafe abortions.

“What you might see, I’m sorry to say, is more funerals. You may see an increase in maternal deaths. Unsafe abortions may result in complications such as hemorrhaging and infections.”

The church member has worked at multiple Planned Parenthood clinics — first as an intern during graduate school, and then later as a volunteer when she moved to Chicago.

While she supports a woman’s right to make decisions about her own health care, none of the clinics where she worked performed abortions, Johnson said. Instead, they offered women access to health care services including contraception, mammograms, testing for sexually transmitted diseases and sex education.

Education, Johnson said, is vital to reducing the number of women in need of an abortion.

“I helped a young mother get free birth control because her family has no insurance, and they couldn’t afford additional children,” Johnson said. “I held a 40-year-old woman’s hand when she had her first mammogram.

“Abstinence isn’t realistic for most, unfortunately, and leaves our teens especially without the information and skills that they need. Let’s prevent unwanted pregnancies by educating both genders.”

Johnson describes herself as “truly pro-life.” In her opinion, some politicians who support abortion bans are unwilling to enact or to support policies such as access to health care and basic necessities like affordable housing, food and child care.

“Once birth occurs, they are no longer pro-life; they’re only pro-birth,” she said.

“I believe that once birth occurs, it is up to us as a society to ensure that these children and their parents have what they need to be successful.”

This piece is republished with permission from The Christian Chronicle. Audrey Jackson, a 2021 journalism graduate of Harding University in Searcy, Arkansas, is the Chronicle’s associate editor for print and digital.