This Innovative Christian Homeless Shelter Is Rising To California's Housing Challenge

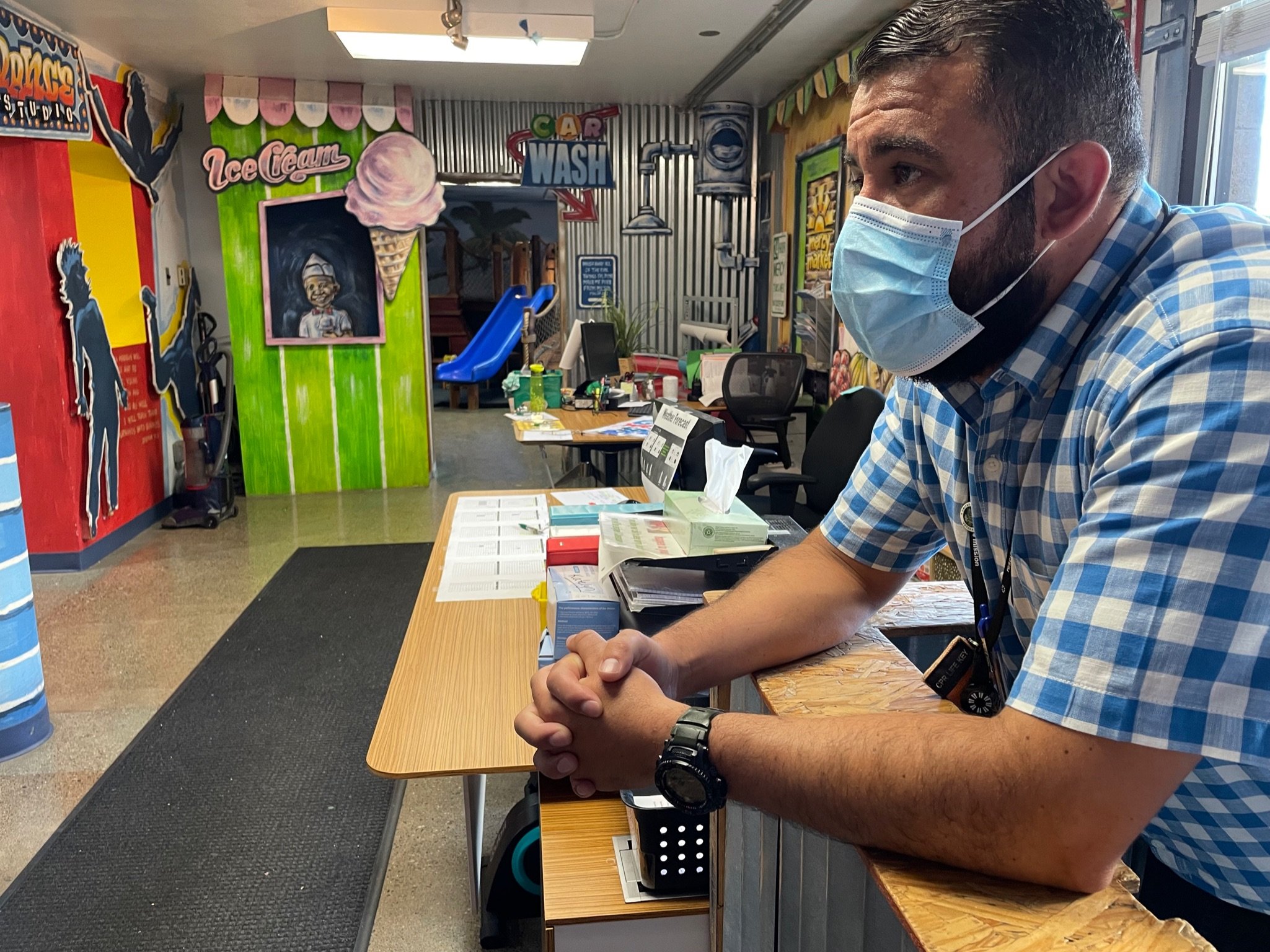

Murrae Glenn. Photo by Paul Glader.

TUSTIN, Calif.— In 2013, Murrae Glenn lived in a warehouse-style homeless shelter in Los Angeles’ skid row. Now, she works as a chef manager for NBCUniversal and rents a one-bedroom apartment in Pasadena.

She credits her turnaround to God and the Orange County Rescue Mission, an innovative Christian homeless shelter based in Tustin with several other locations. The Tustin campus, known as the Village of Hope, runs without government funding or private debt and employs an organizational and aesthetic ethos that more closely resembles a college campus than a homeless shelter.

According to data collected by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, homelessness in California increased by 6.8% between 2019 and 2020, the states’ largest year-over-year increase on record. The same report found that California accounts for more than half the homeless people in the country.

With 12 campuses across the county, the Orange County Rescue Mission plays a vital role in combating the crisis. The Village of Hope alone houses up to 270 men, women and children as part of its residential, back-to-work recovery program.

Homeless Shelter or Vintage Mansion?

In 1991, the mission received a conditional use permit for a new property to house women and children, not realizing until it was too late that it had purchased land in a historic district. Due to regulations, the mission had to emulate a 1940s Craftsman-style mansion.

When the facility opened, women would come into the manor-style living room for the first time, gaze up at the winding staircase, drop their bags and sob.

“After the third time this happened, we were like, ‘What is going on?’” said Jim Palmer, president of the Orange County Rescue Mission. “Turns out they were just so overwhelmed with the beauty and the feeling of safety … that their self-esteem took a boost to a level that, pragmatically, would take us a year to get to.”

A breakthrough that other residents, called students, often wouldn’t experience until after prolonged counseling and adjustment, these women felt instantly. At that moment, Palmer and the rest of the organization committed to cultivating beauty in their spaces.

This commitment to aesthetic design sets the village apart from other, warehouse-style emergency housing facilities.

Past the metal detectors and motion-sensing thermometers at the Village of Hope, additions since the COVID-19 pandemic, the admissions office opens to a beautiful courtyard landscaped by students. The village is separated from the parking lot by 8,000-pound, meticulously crafted steel gates. A 16-foot, 16,500-pound porcelain urn — the largest in the world according to the World Record Academy — sits outside the community chapel. It usually runs with water but was dry all summer because of the California drought.

Students mill around the yard, wearing color-coded lanyards to denote their progress in the program: Freshmen are yellow, sophomores are green, juniors are blue and seniors are red.

Each student has an assigned job on campus for 40-45 hours a week, ranging from audio-visual support to kitchen staff to office and accounting positions. They report to supervisors, complete job training and, as a team, keep the campus running.

During her time at the village, Glenn worked the evening shift in the dish pit. She remembers praying, singing, and occasionally yelling at God under the cover of the mechanical rumbling during her early days in the program.

Eventually, she became a prep-cook and assistant chef, learning the skills that led her to a culinary career.

Before Orange County Rescue Mission took over the campus, it was a decommissioned Marine base. Upon its arrival, the mission converted the two barracks into apartment-style dorms and transformed the brutalist architecture into something resembling an elite university.

“I wouldn’t want to put any homeless person into a room or a facility that I wouldn’t be comfortable staying in,” Palmer said, during an interview in his office. “So I started a practice of always staying in the facility before we open it up.”

It’s All About Fundraising

At the age of 14, Palmer had his first encounter with homelessness.

His friend Michael lost his father to suicide after the family business went bankrupt and Michael and his mother faced eviction.

Palmer tried to consult anyone he thought might help: teachers, the principal, the mayor’s office (who didn’t return his phone call) and eventually the executive director of the local Boys and Girls Club.

Palmer remembers asking him, “How do you help people? How does a nonprofit work?”

In Palmer’s memory, the man laughed and said, “Well, it is all about fundraising.”

At that moment, Palmer began to learn everything he could about the process.

“I also formed a couple of my own businesses because it seemed like the fundraising was taking too long,” Palmer said.

At 18, he started working for a nonprofit called Irvine Temporary Housing. At 19, he was serving as the executive director.

Hear another story from the Orange County Rescue mission on the Religion Unplugged Podcast: Apple Podcasts | Stitcher | Spotify | Google Podcasts

When Palmer took over the Orange County Rescue Mission in 1992 in his late 20s, the organization was in debt and struggled to finance its operations. Palmer says he made a deal with God and committed to an unconventional funding philosophy:

If God would help him out of the mess, he would never borrow another dollar. This promise, combined with a pragmatic avoidance of government funds, made the village one of the few privately-funded shelters of its size in the country.

“We don’t use government funds because they have a lot of red tape — how you can help someone, who you can help, and what it all looks like,” Palmer said.

A tangible memorial to this principle lies buried under the stage of the campus chapel.

In 2001, the mission had plans drawn up to convert the decommissioned military base into a homeless shelter. It worked with the city to navigate local ordinances and federal red tape and made progress toward an opening date. According to Palmer, the city independently decided to get a grant for the project from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The construction plans included a sketch for the campus chapel.

“HUD looked at the plans and said, ‘OK, you can’t call it a chapel. … If you call it a multipurpose room, we’ll look the other way,’” Palmer said. “And I didn’t feel comfortable with that, so I said no. HUD got upset, then the city got upset and impacted our construction for a while. They sort of pulled our permits.”

In an act of coincidence or providence, one of Palmer’s attorneys ended up in the U.S. attorney general’s office in Washington. Before their appointment, during a standard morning prayer time, the group of guests shared prayer requests. Palmer’s attorney asked the congregants to pray for the situation at the Orange County Rescue Mission.

David Kuo, special assistant to then-President George W. Bush, attended the meeting and asked Palmer’s attorney if he could share the request with his boss.

“Before we knew it, the president of the United States was writing an executive order to level the playing field for faith-based organizations,” Palmer said. “And once he wrote that, the federal agencies backed off and the city … and we were able to build our chapel and move forward with our life.”

The village buried a copy of that executive order underneath the stage.

‘They need a higher power’

When potential students arrive at the Village of Hope, they complete a self-assessment and consent to a background check that scans for violent or sexual crimes. According to the village, 87% of students self-identify as having a mental health problem, an addiction problem or both.

According to data compiled by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 38% of homeless individuals are dependent on alcohol, and 26% abuse another drug.

Despite these statistics, Orange County Rescue Mission has reported a remarkably low recidivism rate.

Based on a post-graduate survey, 85% of graduates are still self-sufficient two years after leaving the mission. The survey defined self-sufficiency by a list of factors, including steady employment, stable housing, involvement in the community and sobriety.

Palmer credits the organization’s success to its spiritual dimension.

“We see such a high success rate because (when) those that are so broken that come to us, they don’t feel like they have the capacity to deal with all they are dealing with,” Palmer said. “They need a higher power. They need to have faith in something more powerful than themselves.”

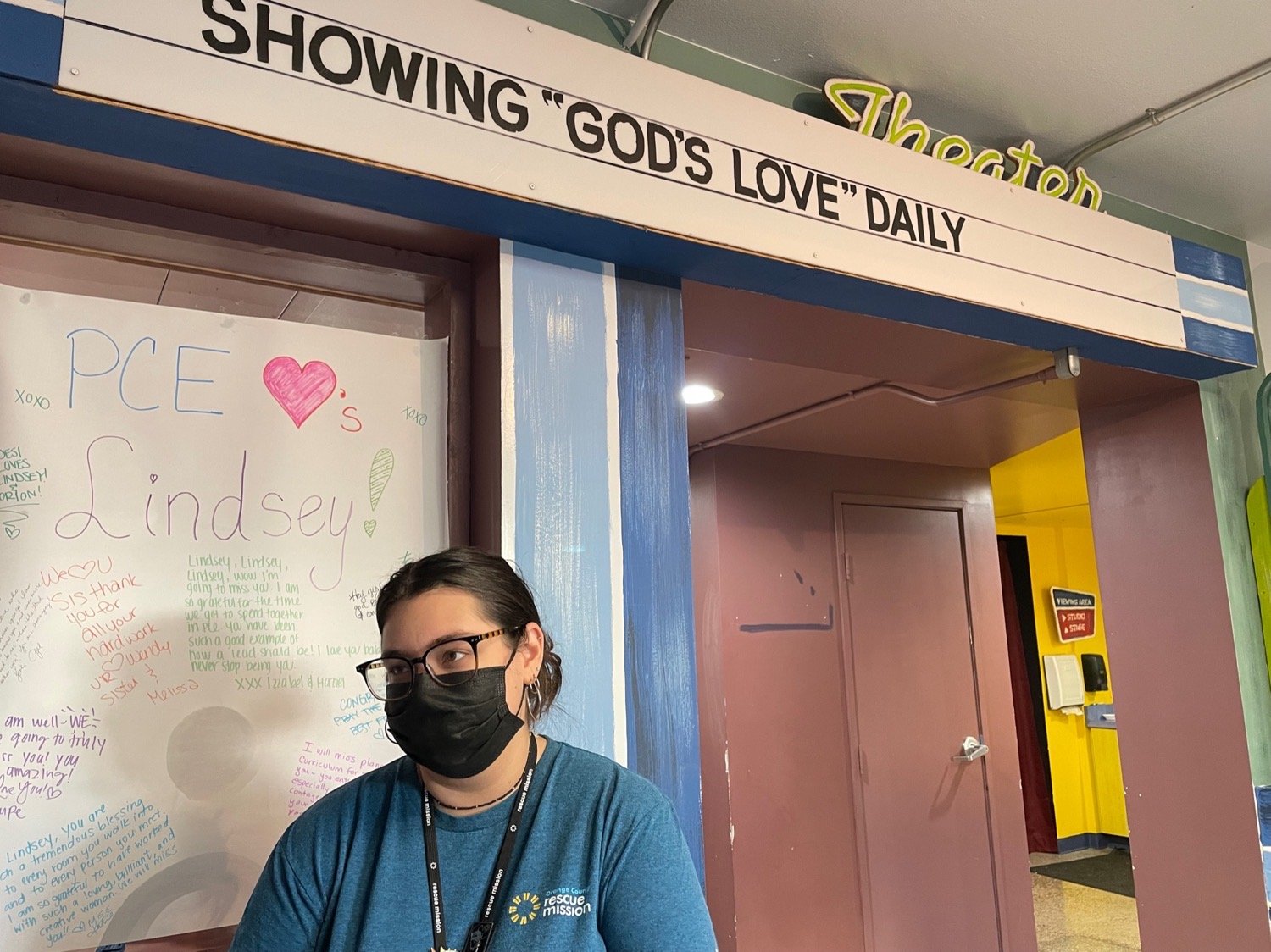

In addition to counseling, job training and opportunities for ongoing education, the mission hosts weekly chapel meetings that are compulsory for students. Upon their arrival at campus, students receive a document resembling a course map that outlines the responsibilities and privileges given to freshmen, sophomores, juniors and seniors and the requirements to progress through the program. It also outlines the mission’s Christian commitments.

Most students complete the program in two years, but some stay for as long as five years. Upon completion, the mission honors students with a cap-and-gown ceremony and a certificate from “The Mission University.” They then have the option to join an alumni network of other graduates with a standing invitation to return to campus for visits or volunteer work.

After leaving the mission in 2015, Murrae Glenn returned weekly for years to prepare meals in the kitchen where she first learned how to cook. Her first work assignment in the dish pit gave her a private space to process her emotions while working with her hands.

“It was so loud back there,” Glenn said. “I could sing or yell at God or do what I needed to do to get right. It gave me something to focus on while I went through it.”

After a few months doing dishes, she switched jobs to assist the visiting chefs who volunteered to make dinners. She fell in love with the kitchen and gained the practical experience to cook professionally.

Over the summer, she received a promotion to oversee the Terrace Cafe and all of the cold catering for the NBCUniversal cast and crew.

“It was God who did the work in me, but I owe a lot to the Orange County Rescue Mission,” Glenn said.

Liza Vandenboom Ashley is a graduate of The King’s College in New York City and the recipient of the 2020 Russell Chandler Award from Religion News Association for excellence in student reporting.