‘Everywhere Is Heaven’: The Art Of Stanley Spencer And Roger Wagner Join Forces

(REVIEW) For the first time in its 62-year history, the Stanley Spencer Gallery in Cookham, England, is collaborating with a living painter. The exhibition, “Everywhere is Heaven,” pairs Stanley Spencer’s visionary paintings with those of Roger Wagner, whose work is deeply inspired by Cookham’s most famous son and similarly transposes events from the Bible to contemporary settings.

Spencer described the charming Thames-side village of Cookham in Berkshire, where he was born and spent much of his time, as “heaven on earth,” and the exhibition opens with one of his earliest paintings, “John Donne Arriving in Heaven” (1911), set on the nearby Widbrook Common. Donne’s metaphysical poetry was much loved by Spencer, and here the Jacobean poet is depicted walking on the common, where four praying figures facing in different directions reflect the artist’s curious sentiment that “everywhere is heaven so to speak.”

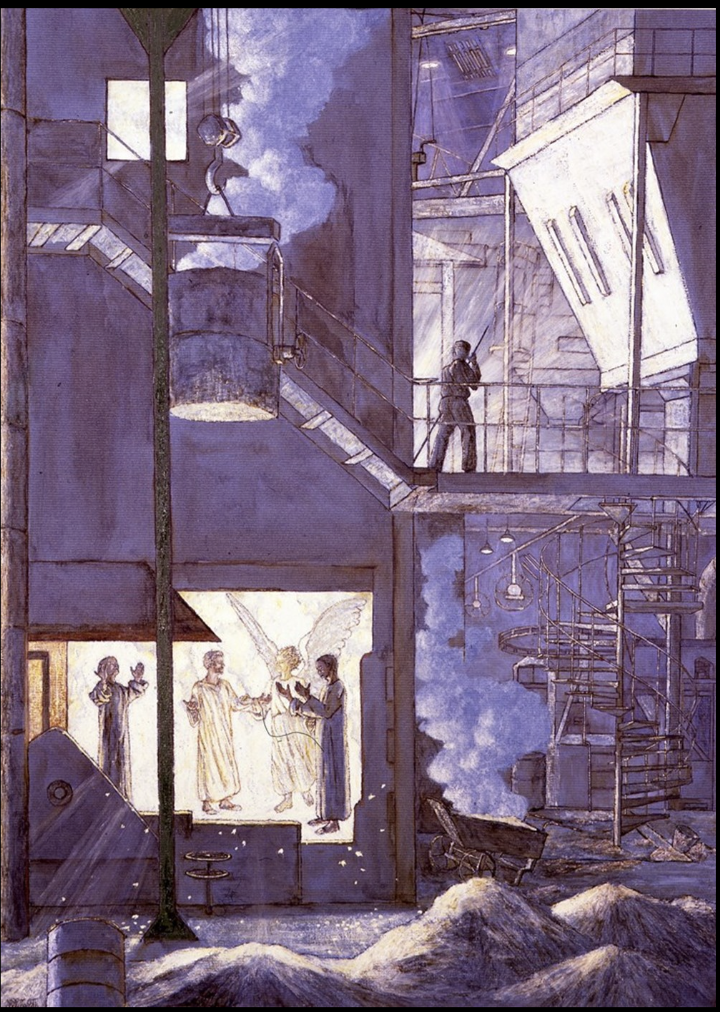

Nearby, a more scriptural notion of heaven is evoked by Wagner’s “Sacred Allegory: Apocalypse (Study)” (2023), a fantastical vision in which the New Jerusalem appears miraculously reflected in a river surrounded by smoke-belching industry. In the foreground, humanity is represented by a procession of shackled prisoners, stumbling along the shore toward a wounded lamb. On the other side of the water, captives are being liberated by angels under the watchful eye of a lion.

READ: The Spiritual Roots Of Marina Abramovic’s Radical Art

While not the subtlest of allegories, the grand redemptive theme of this small painting makes it one of the exhibition’s most hopeful images. Its grimy factories and dirty chimneys recall the ugliness and misery of the Industrial Revolution that William Blake famously decried in his 1804 poem “And did those feet in ancient time,” in which England’s “dark satanic mills” are contrasted with its “green and pleasant land.”

Indeed, poetry is central to Wagner’s approach, and like Blake and Spencer, he combines “ancient time” with the landscape of his own era to explore the spiritual state of humanity.

Wagner has evidently been thinking about heaven for much of his career. His large 1989 canvas, “The Harvest is the end of the World and the Reapers are Angels,” takes as its inspiration the Parable of the Wheat and the Tares, in which Jesus describes how, at the end of the present age, the faithful will be gathered up to paradise while the unbelievers will be cast into fire.

There is no wailing or gnashing of teeth here, though. Wagner has set the scene in rural Suffolk, where he would holiday as a child. Angels are busy reaping wheat in the hot sun, their wings casting strong shadows across the glistening field; one suggests a figure with outstretched arms, an allusion perhaps to Calvary. By now, the “good seed” that Christ spoke of in his parable is evident and easily separated from the weeds, which appear in the murky shadow of the foreground.

Wagner first encountered Spencer’s paintings as a student when the Royal Academy in London held a major retrospective of his work in 1980. He was immediately drawn to the artist’s penchant for imbuing everyday life with spiritual significance.

“Here was an artist who seemed to be doing exactly what I wanted to do,” he said, remembering how he marvelled at “the almost playful way in which he was able to bring medieval religious imagery into contemporary Cookham.”

Wagner has evidently been influenced by Spencer’s approach. Yet while there are formal similarities between these two figurative artists, he has forged a singular artistic identity, similarly without kowtowing to popular trends.

Where these two artists most complement each other is in their transplanting of Middle Eastern biblical scenes to English locations of personal significance. In a sketch from 1920, Spencer pictures Christ in Cookham High Street, carrying his cross like a workman with a ladder. Wagner, in “Walking on Water III” (2005), depicts the savior with St. Peter, miraculously standing on the River Thames with Battersea Power Station towering behind them. These are jarring scenes, strange anachronisms that catch us off guard.

Yet they are not really that different to the majority of European religious paintings, which typically recast episodes from the New Testament in Western settings. Take 15th-century Italian artist Piero della Francesca, who depicts Christ’s baptism taking place in the Italian countryside rather than the Jordan River, or Leonardo da Vinci, whose famous “Last Supper” (1495–1498), shows Jesus and his disciples sitting at a long, Italian trestle table as opposed to reclining on cushions around a low table as was the custom in first-century Judea.

Spencer’s own “Last Supper” (1920) is an idiosyncratic composition in which the famous Passover meal celebrated by Christ and his disciples is relocated to one of the Cookham malthouses that he could see from his home. The disciples seem uncomfortable in the tightly packed scene, their legs outstretched and their toes, almost touching, forming a kind of ladder that leads our eye toward Christ who is breaking bread at the head of the table.

Whereas Cookham represented an earthly paradise for Spencer, Wagner shows us glimpses of the heavenly amid a broken world. His compositions, conveying as they do a yearning for redemption, thus act as a foil to Spencer’s.

“For me, the intrusion of industrial technology into the world has provided imagery for all that challenges our humanity,” he said of the dehumanizing industrialization he depicts.

Though his factories and power stations represent humanity’s proclivity for spoiling God’s creation in the name of progress, they also offer for him “the possibility of a strange redeeming beauty,” he added.

Spencer may have seen heaven “everywhere,” but Wagner’s paintings call to mind the words of St. Paul in 1 Corinthians 13, which remind believers that the “perfect” is yet to come. Together, these two artists point to heaven, not as an ethereal realm but as a tangible, concrete reality.

“Everywhere is Heaven: Stanley Spencer & Roger Wagner” is at the Stanley Spencer Gallery, Cookham, England, through March 24. Visit the Stanley Spencer Gallery website for more information.

David Trigg is a writer and art historian based in the U.K. You can find him on Instagram @davidtriggwriter.